William Henry Jackson is a famous American photographer, known as being the first person to photograph Yellowstone in the American west. William was also a skilled artist and recorded many of the things going on in his life as a young man. Today, his photographs and drawings provide valuable and unique insight into the period of American history when the Civil War was going on, and the country was exploring the west in earnest for the first time as it searched for a national identity to unify every citizen under the banner of the United States.

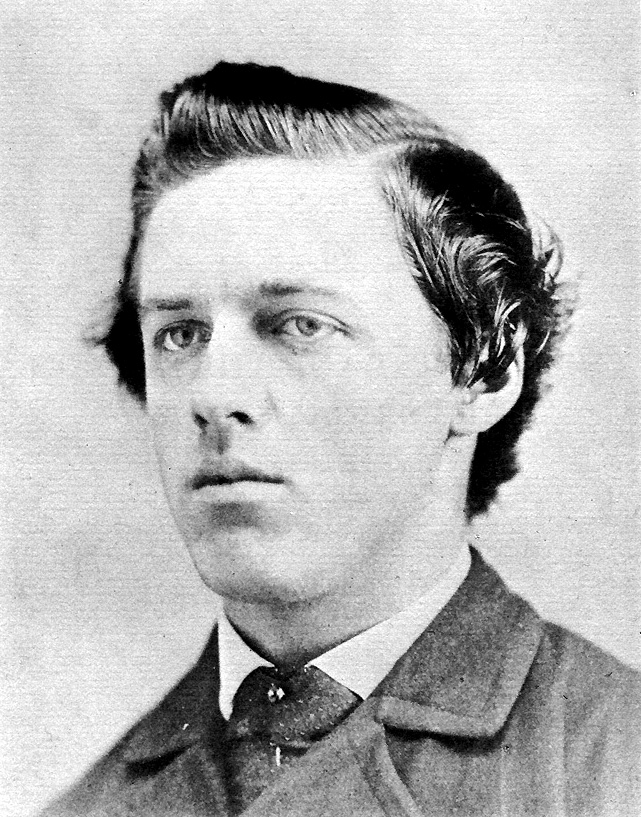

William was born in 1843 in Keeseville, New York as the eldest child of George Hallock Jackson and Harriet Maria Allen. Harriet was an accomplished watercolorist, and William learned this art from her at a young age. In fact, much of his childhood was spent learning to master painting and drawing. When he was ten years old, William was given the gift of lessons in art, where he learned to use perspective, form, composition, and color.

When he was a teenager, William was introduced to photography. In Troy, New York, and Rutland, Vermont, William experimented with this new form of art. In these places, he worked as an assistant in a photographer’s studio where he assisted in setting up and retouching photos. In this job, William also learned how to use darkrooms and cameras, with the techniques and equipment that existed at that time.

As a nineteen-year-old, William enlisted in the Light Guard from Rutland, Vermont. There was not much to do in this part of the country during the Civil War, except for guard duty once in a while. William spent time there drawing sketches of his friends and scenes from his life at the Light Guard camp, which he sent home to show his family and prove that he was still safe. Later in the war, William’s regiment participated in the famous Battle of Gettysburg, though William himself did not take to the field during this campaign. After the war, William went home. His mom saved the drawings he had sent to the family, and they provide today a first-hand account of the life of an infantryman in a Union Civil War camp.

Once he was home, William easily found work in another photography studio. Because he was obviously skilled, he was able to command an excellent salary that allowed him to buy expensive, fancy clothing and live an upper-middle-class lifestyle. After working there for a year, he had already received several large promotions and pay raises, which allowed him the financial stability to attract a girlfriend from a prominent family. Things seemed to be going William’s way in every aspect of his life.

William and his girlfriend got engaged, but a quarrel between them led to them breaking up, and William was too ashamed to face his family after this romantic debacle. In 1866, William left Vermont to look for fortune and seek a new start in the silver mines of Montana. William went there with two friends. They trekked as far as Nebraska City, Nebraska, then signed on as bullwhackers for a freight outfit that was going to Montana. Even though he had no experience with oxen or hauling freight, William soon became proficient at it and was skilled at handling the oxen, particularly.

The change of scenery did wonders for healing William’s broken heart, and he started drawing again, once more sketching the things he saw and encountered on his adventure. Deciding against going to the silver mines, he jumped off the caravan at Wyoming and took a train to Utah and then to California. On this journey, William decided that documenting life in the west as people settled that frontier might just be his passion.

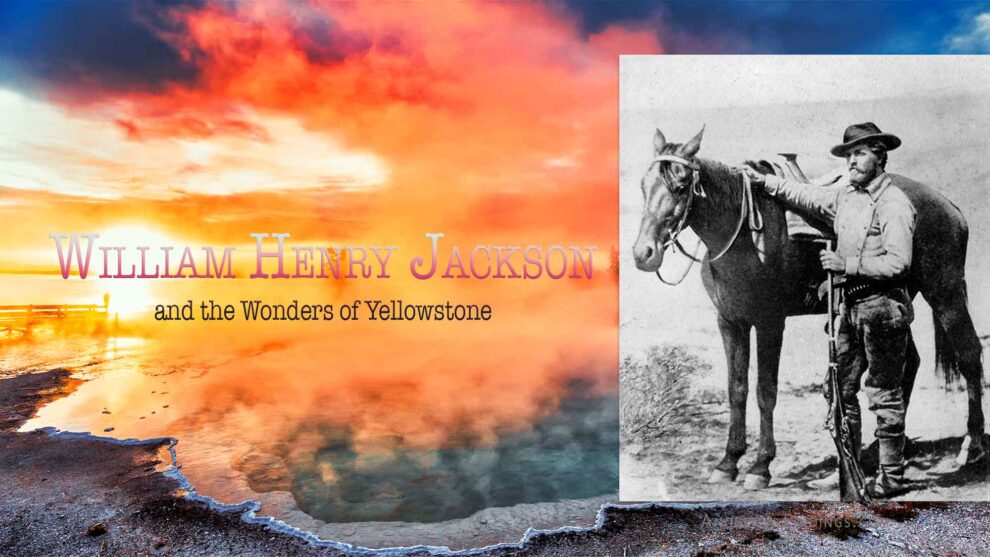

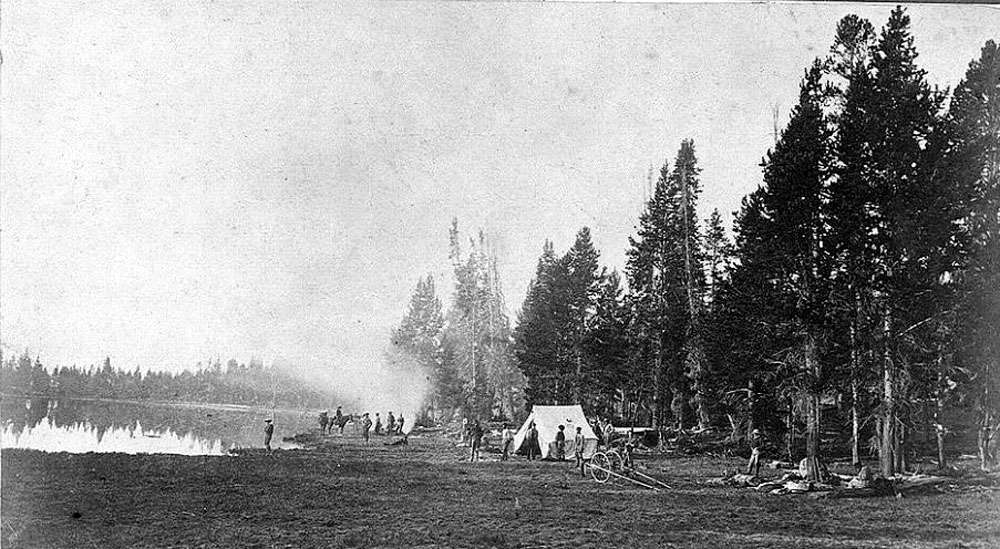

William’s dad sent him some money to assist him in setting up his own photography studio in Omaha, Nebraska in 1869. William started photographing local Native Americans, and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. These photographs earned him an invitation from Dr. Ferdinand Hayden to accompany him on an expedition to explore the wonders of the natural world along the Yellowstone River in Wyoming Territory. Thusly, William went along with Dr. Hayden on the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. The amazing, and at the time, entirely unique, photographs William took of Yellowstone on this expedition earned him the position of official photographer of the US Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories until 1878.

The photographs that William took in Yellowstone became a national sensation. They provided proof that the tales of geysers and waterfalls in Yellowstone were actually legitimate, and not just tall tales like the people in the east always thought they were. So few people besides Native Americans had actually seen Yellowstone at the time, that the few descriptions that made it back east naturally sounded too fantastic to be true. William’s photographs provided irrefutable documentation that they were genuine things.

William’s photographs created such an intense public interest in Yellowstone that Congress officially designated it a national park in 1872, and William’s name became a household word. William continued to travel the American west and take photographs. The most famous of his photographs were taken in 1873 at the Mount of the Holy Cross in Colorado. There had been stories in the east for years about a mountain out west with a large cross etched into it. William climbed the western slope of the Rocky Mountains, which was a daunting task at the time, and photographed an image of this mountain. This proved the existence of the mountain to the public, and prints of this photograph adorned the parlor walls of American homes for years after that.

After William completed his tenure with the US Geological Survey, he opened a photography studio in Denver, Colorado, where he did portrait photography and documented the construction of the railroad and mining towns in the Rockies.

William began a new career as a painter of western scenes when he was eighty-one years old, and moved to Washington, D.C., as he was hired as a muralist there at the age of ninety-four. When he crossed to the other side in 1942 at the age of ninety-nine, survived by his wife and three children, William was one of the last known surviving Civil War veterans. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Mount Jackson, in the Gallatin Range of Yellowstone National Park, is named for William.